By William Boston and Eric Morath

BERLIN--As corporate America debates whether companies should

consider other constituencies than just their shareholders, Germany

offers an example of what a new approach might look like for

labor.

In Germany, where workers enjoy high labor protections and a say

in management decisions, companies such as Volkswagen AG and Bayer

AG have announced plans this year to cut tens of thousands of

jobs.

But rather than resorting to mass layoffs or plant closures,

they will often reach for instruments created by government and

unions that allow executives, often with considerable state

support, to weather economic storms, or reduce their workforces

through voluntary methods.

Yet for influential U.S. CEOs like JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s

James Dimon, who recently vowed to become more stakeholder and less

shareholder focused, Germany isn't just a model. It is also a

cautionary tale. Sparing staff in a short downturn can allow

companies to ramp up activity quickly when demand rebounds without

having to hire and train new workers. But it can also slow

necessary adaptations when companies are faced with structural

changes, resulting in some businesses sticking to outdated business

models for too long, economists and management experts say.

Among the German companies who said this year they will slash

tens of thousands of jobs are auto giant Volkswagen, car parts

suppliers Continental AG and Robert Bosch GmbH, pharmaceutical

company Bayer, electronics group Siemens AG, chemicals maker BASF

AG, and business software maker SAP SE.

However, most of them will use short-time work, early

retirement, and other instruments to reduce their workforce or even

keep staff on with government support rather than axing jobs as

U.S. auto giant General Motors Co. did recently when it decided to

shut five plants in the U.S. and Canada.

"There is a social and cultural view in Germany that is

different than the U.S. but also a system of governance where the

interests of the employee is more in the foreground," said Craig

Smith, chair in ethics and social responsibility at Paris-based

business school Insead.

Volkswagen took action early. In 2016, the company said it would

shed 23,000 administrative and factory jobs in Germany by 2025. Hit

by slower demand in China and Europe, Volkswagen slashed production

in its German factories by 15% in the first half of this year and

announced another 4,000 job cuts. When the restructuring is

completed, Volkswagen will have shed 25% of its German workforce

from its 2017 level.

But it won't resort to forced layoffs. Instead of shutting

factories, Volkswagen is retooling three plants to make electric

cars. And it is shrinking the workforce long term by not replacing

the large numbers of baby boomers who are approaching retirement

age.

Bosch employs 50,000 people world-wide just in diesel components

businesses, 15,000 of them in Germany. Management is negotiating

with the IG Metall trade union to reach an agreement on cutting

staff.

Bosch CEO Volkmar Denner said recently that the company is

"doing everything to do this in a way that is socially

responsible," saying the company would use work time accounts,

severance programs, early retirement, and reducing the ranks of

temporary workers.

Notwithstanding the cultural differences, German managers have

little leeway in how they treat staff. Since the 1970s, by law the

supervisory board of any company with more than 2,000 employees

must be made up of equal numbers of shareholder and labor

representatives, which has given trade unions enormous

decision-making influence.

Many of Germany's biggest corporations have brokered deals with

trade unions to allow them to reduce staff through various

instruments in exchange for agreements to ban forced layoffs.

Bayer, for example, is cutting 12,000 jobs by the end of 2021, but

resorting mainly to voluntary methods such as early retirement and

buyouts that in some cases offer up to five years of severance

pay.

"Such voluntary offers are always expensive because they have to

be attractive, otherwise no one would take them," said Georg

Müller, Bayer's Germany human resources chief.

The upside for Bayer, he said, that it gives the company more

control over managing the staff reductions and reduces the

confrontation between management and workforce, preventing costly

and disruptive strikes.

Alternatives to redundancies and plant closures--which are all

possible under German law but can be slow and costly--have at times

helped companies be more rather than less nimble in reacting to

rapid fluctuations in demand.

In 2009, as Germany's gross domestic product collapsed in the

wake of the Lehman Brothers closure, many companies resorted to

short-time work--sending employees home but keeping them on the

payroll thanks to wage subsidies.

Hours worked per employee declined 3.8%, but when demand

rebounded a year later, they could skip a lengthy hiring and

training process. Despite a 5-point drop in GDP, unemployment rose

less than a percentage point, while in the U.S., it rose to a

postrecession peak of 10% in October 2009 from a prerecession low

of 4.4% in the spring of 2007.

Another tool that has become popular in Germany to manage

capacity is working-time accounts, which are typically negotiated

as part of labor contracts. With these accounts, workers can bank

overtime pay during good economic times and then tap those accounts

when their hours are cut during economic downturns.

But the German way also bears risks.

"If you have a structural change--a business model change--then

short-time work could prolong a crisis by avoiding making the

necessary adjustments," said Enzo Weber, an economist at the

Institute for Employment Research in Nuremberg, Germany.

Another limitation is that socially considerate alternatives to

payroll cuts work best in deep and short downturns but can prove

excessively costly--to companies or to the state--in shallow,

protracted slumps when capacity needs to be durably reduced.

"The institutions are set up to create even more flexibility" to

retain workers during slowdowns, said Gunther Friedl, dean of the

Technische Universität München School of Management in Munich. "The

risk is if you keep too many people, and the losses pile up to the

point of no return, that could result in bankruptcies."

Germany's finance minister hinted last month that it had a war

chest of EUR55 billion ($61 billion) to inject into the economy to

buffer the effects of a downturn.

German GDP shrunk in the second quarter and the country's

central bank warned in its most recent monthly report that the

country may already be in a recession. How long it could last is

anyone's guess. There is no sign or a resolution to the global

trade disputes and the slowdown in China that are weighing on

global demand--a particular concern for an economy that is highly

dependent on exports.

"Businesses should be preparing for a recession the next one to

two years," Mr. Friedl said. "Depending on trade fights, it could

be more or less severe."

Ruth Bender

in Berlin contributed to this article.

Write to William Boston at william.boston@wsj.com and Eric

Morath at eric.morath@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 09, 2019 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

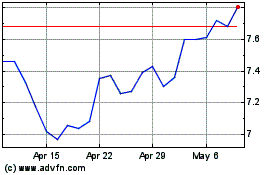

Bayer Aktiengesellschaft (PK) (USOTC:BAYRY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

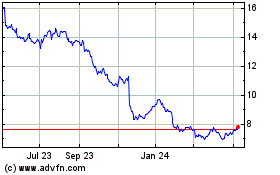

Bayer Aktiengesellschaft (PK) (USOTC:BAYRY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024