By Richard Rubin and Theo Francis

Consumer-products conglomerate Newell Brands Inc., facing $180

million to $220 million in taxes because of Treasury Department

antiabuse regulations, isn't recognizing those costs in its

financial statement, contending the new rules aren't valid.

The move presages a legal fight between companies and the

government. Beyond tax revenue, the outcome may shape the

government's ability to implement some of the most sweeping

provisions of the 2017 tax law while Congress remains deadlocked

over technical fixes.

Newell, which makes Sharpie markers, Mr. Coffee machines and

Rubbermaid containers, told investors this month it was so

confident the government's rules will fall that it didn't have to

take an earnings hit. The tax cost would have swung the company

from profit to loss in the second quarter. Maxim Integrated

Products Inc., an analog chip maker, made a very similar disclosure

to its investors. Neither company would comment beyond public

filings.

Qualcomm Inc. said in a securities filing that the regulations

affected deductions related to a 2018 intellectual-property

transaction. The company agreed with the Internal Revenue Service

to forgo benefits of that transaction and took a $2.5 billion

charge. Qualcomm said it decided that complying with the regulation

was in the company's best interest.

Other companies flagged the new rules -- which are retroactive

to the end of 2017 -- in securities filings, though less clearly.

LyondellBasell Industries NV, a chemical company, and IHS Markit

Ltd., an information provider, disclosed that they may be affected.

More may file public comments to the government before a

mid-September deadline.

Accounting experts say that, in general, companies are expected

to recognize expenses once they are quantifiable and sufficiently

likely to occur.

"If it's probable and reasonably estimable, you're supposed to

do it," said Janet Pegg, an accounting analyst with Zion Research

Group. By concluding that the regulations are likely to fall,

companies may be able to convince their auditors to sidestep

recognizing the expense.

A spokeswoman for the Financial Accounting Standards Board,

which determines U.S. generally accepted accounting principles,

declined to comment on the companies' positions. A spokeswoman for

the Securities and Exchange Commission and Treasury officials also

didn't comment.

The corporations' complaints are the leading edge of a legal

challenge to the temporary, retroactive regulations, which the

Treasury released in June to stop and overturn what it saw as

abusive transactions made during gaps created by the 2017 tax

law.

The Treasury released the rules in mid-June, just days before

the deadline for imposing retroactive regulations back to the

enactment of the 2017 law. They resemble a January 2019 proposal

from Rep. Kevin Brady (R., Texas), a chief author of the tax law.

Congress hasn't acted on that or other changes because lawmakers

disagree over what to include in a technical-corrections package

and what other proposals to pair with it.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is examining the Treasury's

regulatory authority and exploring options to ensure a

business-friendly result, said Caroline Harris, the group's chief

tax counsel.

"Treasury wants to make this whole statute work," said David

Rosenbloom, an international tax lawyer at Caplin & Drysdale in

Washington. "They're basically stepping in and doing the job that

Congress didn't do."

One portion of the complex regulations aims at companies taking

advantage of a timing gap in the law by shifting profits into a

period when they could avoid U.S. taxes that would otherwise

apply.

The 2017 law created a territorial tax system, so that U.S.

corporations can send foreign profits to their domestic parents

without paying U.S. corporate taxes.

However, the law also created a minimum tax on foreign income.

That is intended to prevent companies from avoiding U.S. taxes on

profits from places with low tax rates such as Singapore and

Ireland.

Here's the catch: The territorial system started Jan. 1, 2018,

but the minimum tax didn't. Instead, it took effect based on the

fiscal year of companies' foreign subsidiaries, starting with the

first tax year beginning after Dec. 31, 2017.

Because many foreign subsidiaries have fiscal years ending Nov.

30, 2018, they had a one-time opportunity. They had nearly a year

when could earn low-taxed foreign income and bring the money home

without paying U.S. taxes.

"Once you saw that mismatch, that was the main ingredient and

environment you needed for the planning," said David Sites, an

international tax partner at Grant Thornton LLP.

There is no public data on what companies did, though the

Treasury rules said the government was aware of transactions that

have the potential to substantially undermine the purpose of the

tax law. Mr. Sites said some companies acted but the vast majority

won't be affected.

Still, U.S. corporate tax receipts for tax year 2018 were

unexpectedly soft, even considering the tax cut.

The Treasury's rules didn't attempt to tax all profits companies

earned during the gap in the law. Instead, they focus on what the

government deems extraordinary transactions, often achieved by

selling intangible assets from one foreign subsidiary to another.

Other parts of the rules apply more broadly.

Newell and Maxim both wrote in securities filings that they

believe they have strong arguments in favor of their position,

enough to conclude that they are more likely than not to prevail in

any challenge to the tax position they have taken. A court case

could turn on the government's regulatory authority to implement

congressional intent, the viability of retroactive regulations and

the question of whether the language of the statute was so clear

that the Treasury and IRS didn't have any ability to act.

Both companies also cautioned that the outcome is uncertain.

Maxim didn't estimate a cost and neither did IHS Markit.

LyondellBasell said it was permanently reinvesting money in an

offshore subsidiary because of the rules, preventing a $60 million

tax cost.

"This will be litigated," Mr. Rosenbloom said. "This is not

going to go down like chocolate sauce."

Write to Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com and Theo Francis

at theo.francis@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 30, 2019 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

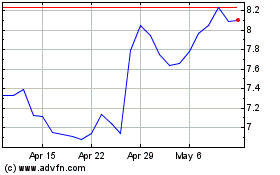

Newell Brands (NASDAQ:NWL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

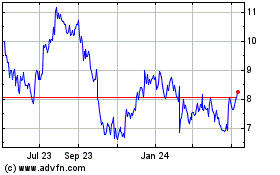

Newell Brands (NASDAQ:NWL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024