By Greg Ip

At the peak of the tech bubble in 2000, Microsoft Corp. jockeyed

for the title of world's most valuable company with Intel Corp.,

which made microprocessors; Cisco Systems Inc., which made

communications gear; and General Electric Co., which made

locomotives and turbines.

Nearly two decades later, Microsoft is once again atop the

market-value rankings. Cisco, Intel and GE are -- combined -- worth

about half of Microsoft. This signifies a profound shift in the

economy in recent years. Productivity and economic growth

increasingly flow not from equipment, buildings or computer

hardware, but from instructions, processes, coding and data: in

other words, software.

Nearly eight years ago, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen

wrote: "Software is eating the world."

Software programming tools and Internet-based services such as

cloud computing, he argued, enabled start-ups to displace

incumbents by digitizing everything from phone calls and cars to

retailing and film distribution.

Like-minded technological evangelists have long argued

artificial intelligence, machine learning, big data and other

technological advances were about to unleash a new boom. But the

boom refused to show: growth in productivity -- the best measure of

how technology enhances worker output -- remained mired near

generational lows.

Recently, however, there have been intriguing signs a boom may

be in the offing. In the first quarter, American companies for the

first time invested more in software than in information-technology

equipment. Indeed, outside of buildings and other structures,

software surpassed every type of investment, including

transportation equipment such as trucks and industrial equipment

such as machine tools. Software spending is even higher if the cost

of writing original software programs, now classified as research

and development, is included.

Adjusted for inflation, software investment grew 11% from the

first quarter of 2018 through the first quarter of 2019. By

contrast, investment in equipment grew less than 4% and in

structures, just 1%. (Revised data are due out Thursday.) The

headwinds buffeting capital spending broadly, whether the waning

tax cut, trade war or slumping commodity prices, have largely

spared software. Meanwhile, productivity growth has picked up to

2.4% in the past year, the fastest since 2010.

Whether that can continue is debatable: business investment and

productivity growth appear to have slowed in the current quarter.

Nonetheless, a recent survey by Morgan Stanley & Co. found

chief information officers planning to boost software budgets this

year by 5%, and hardware budgets just 2%. Their main target is

cloud computing, under which businesses pay external providers to

host their data and supply tools to analyze that data.

Microsoft years ago wouldn't have been seen as an obvious winner

from this shift. Long reliant on Windows and its Office software,

it had flubbed the transition to web-based applications, mobile and

search. Amazon.com Inc. grabbed an early lead in offering cloud

computing as a standardized service to the public. In his 2011

article Mr. Andreessen said Microsoft was "threatened with

irrelevance."

After Chief Executive Satya Nadella took the company's reins in

2014, Microsoft shifted focus to cloud-based services. Dubbed

"Azure," the services now account for half of the company's

revenue. Microsoft lacks the hipness factor of consumer-facing

Amazon, Alphabet Inc.'s Google and Apple Inc. Yet it has achieved

comparable growth by making itself a partner for businesses bent on

"digital transformation," a nebulous term that means using

technology to remake processes or products.

Starbucks Corp. uses Azure to centrally monitor coffee machines

for everything from the type of bean to coffee temperature and

predict needed maintenance. The company used to deliver new coffee

recipes manually by sending USB thumb drives to 30,000 stores. Now,

they are delivered through the cloud. The Starbucks mobile app uses

a type of machine-learning system hosted by Azure to show customer

recommendations based on store inventory, weather and the user's

order history.

If there is a constraint on this boom, it's that software is

harder to get right than hardware. Because big companies often

customize or design their software in-house, their success may be

difficult for others to replicate. A study by James Bessen at

Boston University found that companies that invest more in

proprietary information technology enjoy faster profit growth,

higher revenue per employee and wider profit margins. Smaller firms

struggle to compete against those advantages, which Mr. Bessen says

is why economic activity has become concentrated in fewer

firms.

Cloud computing could alter that equation by extending

capabilities currently the preserve of big companies to small and

medium-size firms. Libbey Inc., a Toledo, Ohio, manufacturer of

wine glasses, tumblers and other tableware with 6,000 employees and

six factories worldwide, is replacing multiple sales, finance and

production computer systems with a single cloud-based system from

Microsoft that will enable employees to see the entire company from

anywhere in the world. The benefits will include faster response by

salespeople to customer requests, reduced inventory and less manual

processing of transactions, says James Burmeister, Libbey's chief

financial officer.

Libbey can buy most of the necessary software "out of the box"

from Microsoft without having to "make any custom code," he says.

However, Libbey will likely need programmers and data scientists to

design and optimize tools to analyze the data that Azure gathers,

using its algorithms to squeeze the cost out of making glasses. "We

want to get rid of the manual task at the bottom of the food chain,

and elevate the work of our people into...running the business

better," he says.

There's no guarantee the money now being plowed into software

will achieve the kind of payoff that hardware did two decades ago.

But at least it's headed in the right direction.

Write to Greg Ip at Greg.Ip@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 29, 2019 10:58 ET (14:58 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

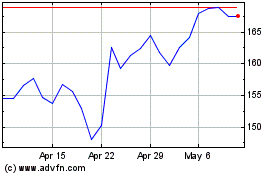

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024